By Davida Spaine-Solomon

Freetown, 16th October 2025- The Kingtom Ebola Cemetery, once a solemn resting place for hundreds of Sierra Leoneans lost to the Ebola epidemic, now stands as a symbol of conflicting truths.

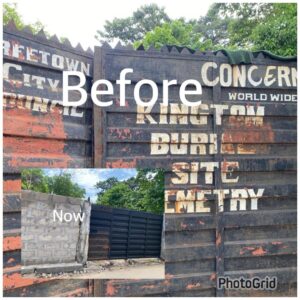

Depending on whom you ask, or where you stand within its perimeter, the site is either a transformed memorial or a neglected hazard. The Freetown City Council insists it has rehabilitated the cemetery, pointing to new fencing, a redesigned gate, and recent clearing efforts. But a visit by Truth Media reveals a more complicated reality, one that doesn’t quite match the official narrative.

On one side, the cemetery does show signs of improvement. The fence is new, the entrance more secure, and parts of the grounds appear brushed and cleared. But walk a little further, and the transformation begins to unravel. The section where most Ebola victims were buried remains overgrown, flooded, and strewn with waste. Pools of stagnant water collect near graves, and the smell of decay hangs in the air. It’s a cemetery of two faces, one polished for public relations, the other left to rot.

For residents living around Kingtom, the contradictions are not just visual, they’re visceral. During the rainy season, floodwaters from the cemetery spill into nearby homes, carrying foul odors and, they fear, disease.

“This happens every rainy season,” one resident told Truth Media, frustration etched into his voice. “The water from the cemetery enters our compounds. We’ve complained for years, but no one listens. They only come around when journalists visit.” To locals, the cemetery is no longer a sacred space, it’s a dump site. Their anger is not just about sanitation; it’s about being ignored.

City officials defend their efforts. Georgiana Johnson, Deputy Environment and Sanitation Officer, explained that brushing, the clearing of overgrown vegetation was last done in May and June, and resumed again in September.

She noted that grass grows quickly during the rainy season, partly due to the human remains beneath the soil. Her explanation, while technically sound, does little to comfort those living with the consequences. The complexity of maintaining such a site is clear, but so is the frustration of those who feel abandoned.

Mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, speaking to Truth Media, was unequivocal in her assessment: “The Ebola Cemetery at Kingtom has been totally transformed,” she said. “A new fence has been built, and a new, well-designed gate has been installed. It’s no longer as accessible as before.” But the mayor’s words clash with what Truth Media saw on the ground. The transformation, if it exists, is incomplete. The contrast between the maintained section and the neglected burial grounds raises uncomfortable questions. If the cemetery has truly been transformed, why are parts still submerged in waste and floodwater? Why does one section receive attention while another, arguably the most sacred, remains untouched?

The contradictions are not just about landscaping. They speak to deeper issues of accountability, transparency, and respect. The cemetery was once a national symbol of grief and resilience.

Today, it risks becoming a monument to neglect. As city officials praise their efforts, the reality in Kingtom tells a different story, one of partial progress overshadowed by years of silence. And for the families who lost loved ones to Ebola, and for the communities still living in its shadow, that silence is deafening.

Until the entire cemetery is treated with the dignity it deserves, not just the parts visible from the gate, the transformation will remain incomplete. For now, Kingtom stands between commemoration and decay, caught in the contradictions of a city still struggling to reconcile its promises with its actions.

It is pragmatic to cremate or incinerate EBOLA VI CTIMS and saves maintenance costs, etc.