Travelogue: Pakandae– By Chernor Bah

There are trips.

And then there’s a trip.

This week, after our retreat on stunning Bonthe Island, I took a day off to go somewhere that has lived in my family lore for years, real in stories, imagined in my head. Until now.

Pakandae.

A tiny, remote village in Sittia Chiefdom. The shortest route is a speedboat from Bonthe, supposedly 15–20 minutes. In reality, closer to an hour and a half. Fewer than 75 people live there. No formal school. Until recently, no functional water well. A fishing community, everyone either fishes or lives by the rhythm of those who do. Shebro is spoken there; Mende comes second.

My father’s mother, Marie Sheriff (of blessed memory), was born and raised there. When she was pregnant with my dad, she travelled from Bonthe back to Pakandae to deliver her first child. The house my father was born in, over six and a half decades ago, still stands. Worn. Weathered. Standing.

The boat ride felt endless. My uncle, who was steering and is himself a fisherman, had confidently told us it would be quick. One hour in, I asked how far we were. He muttered, “Just after the next four villages.”

I laughed. I remembered the old truth about directions in these parts: everything is always much closer than it actually is.

Almost one hour forty-five minutes after we left, he finally pointed to a narrow opening and told the boat to head in. By then, we were fully in the Atlantic, Google Maps and the waves confirmed it.

As we pulled in, I felt relief. And something heavier.

Almost everyone in the village, about 50 people, was lined up at the shoreline, waiting. Welcoming their son.

My late grandmother’s oldest surviving sister still lives in the house. She looks eerily like my grandma. For a moment, it felt like I was meeting someone long gone. They loved up on me and on my friends who had dared this journey. Everyone wanted a piece. I wanted to absorb everything.

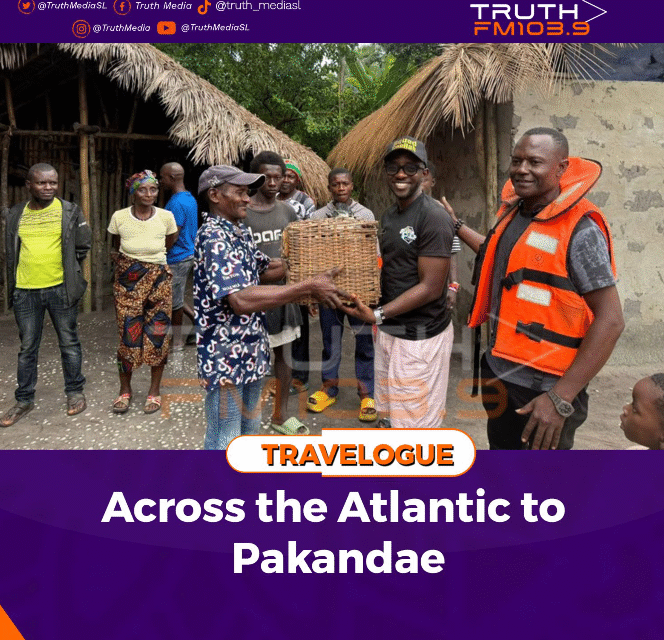

I lay in a hammock they said had been there forever. I broke banga and chewed it. Walked from house to house. Learned Shebro greetings. Presented the famalo we brought to my uncle, now the head of the clan. They prayed for me. Again and again.

Then I almost committed a cardinal sin.

We announced we had to leave, before food had been served.

Part of the panic was logistics. My colleagues were waiting in Bonthe. I had grossly underestimated the trip. And there’s always the risk of getting stuck if the water drops, boats don’t move until it rises again.

Common sense prevailed. We agreed to “take a few spoons” and go.

Ladies and gentlemen, those few spoons turned into a feast.

After the first bite, all five of us knew we were in trouble. One of the most delicious meals any of us had ever eaten. Impossible to properly describe. Fresh. Organic. No Maggi. Groundnut soup that made no sense, with country fowl that had lived a full life. We finished everything. Then reinforced.

For years, Pakandae felt distant. Almost fictional. Like a place from folklore or a children’s tale.

This trip made it real.

I’m humbled that I’ve been able to construct the first borehole tap there, now serving Pakandae and six surrounding villages. I’ve committed to doing a second. We will build a mosque. And within the next year, we’ll push to get a school.

Their parting gift: a carefully curated box of six big, live country chickens.

And something else, unmistakable, unfiltered love.

The kind you don’t question.

The kind you feel in your bones.

The kind I didn’t realize how much I needed.

Thank you, Pakandae.

I’ll be back.