By Kelfala Kargbo

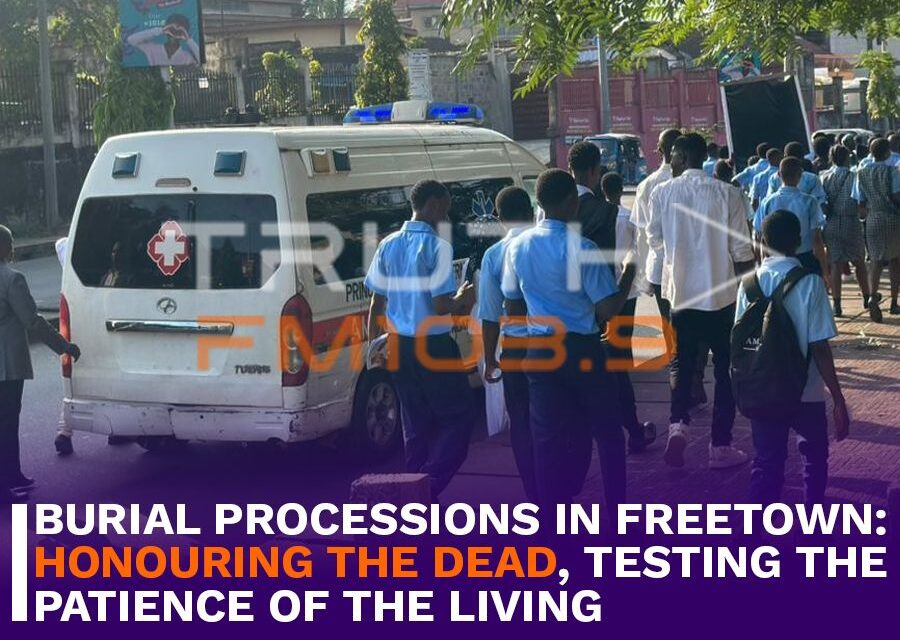

Freetown, 17th November 2025- It was a solemn moment in Wilberforce. Mourners flooded the streets to bid farewell to Tamba Weh, a beloved figure whose life was cut short in his prime. As his body was loaded into a van, a slow-moving motorcade of mourners followed behind, weaving through Bottom Mango. Within minutes, the road was gridlocked. Cars stalled, bikes idled, and horns blared in frustration, a familiar scene in Freetown’s funeral culture.

“For as long as I can remember, people have always walked behind the dead to the cemetery,” said Foday Mansaray, a longtime resident. “It’s how we show respect.”

But in a city already strained by traffic and poor road infrastructure, the age-old tradition of funeral processions is sparking debate. Is it a sacred rite, or a civic nuisance?

A Tradition That Walks Through Time- Across cultures, burial rituals reflect deep spiritual and communal values. In Hindu tradition, male family members carry the deceased on bamboo litters to the cremation ground. In Madagascar, the Famadihana people famously “dance with the dead,” celebrating life even in death.

In Sierra Leone, despite its ethnic diversity, one practice remains consistent: mourners walk behind the corpse, often from the family home to the cemetery. It’s a gesture of honour, solidarity, and spiritual duty.

But not everyone is on board. One Freetown resident recalled attending a burial where drivers caught in the procession grew visibly angry. “People were frowning and honking at us to move faster,” he said. “But culture shouldn’t be compromised for convenience.”

Public Opinion: Split Between Reverence and Reform

A recent survey by the Institute for Governance Reform (IGR) revealed a city divided. While 54% of respondent’s support maintaining traditional burial processions, 46% favour some form of change. Among those calling for reform: 33% suggest limiting roads and times for processions, 8% advocate for a complete ban and 5% propose vehicle-only processions

At a press briefing, IGR Executive Director Andrew Lavalie said the poll aimed to highlight how funeral processions affect urban mobility. “It’s about finding balance,” he noted.

Faith, Frustration, and the Final Journey- For Ibrahim Koroma, a motorbike rider who frequently plies the Wilberforce–Lumley route, the processions are more than tradition, they’re a spiritual duty. “In Islam, following a corpse to the cemetery brings reward,” he said. “Traffic delays are a small price to pay for honouring the dead.”

Koroma believes death is a universal experience, and the few minutes of inconvenience should be met with patience, not protest.

What the Law Says- The Public Order Act of 1965 exempts funerals from requiring police clearance for processions. However, Section 17(6) mandates that participants keep to the left side of the road and follow police directions to minimize disruption.

The law also warns that anyone who interferes with traffic during a procession may be committing an offence, a reminder that tradition must still operate within legal bounds.

Between Culture and Congestion- As Freetown continues to grow, the tension between cultural preservation and urban practicality will only intensify. Burial processions, once a quiet march of reverence, now walk a tightrope between honouring the dead and inconveniencing the living.